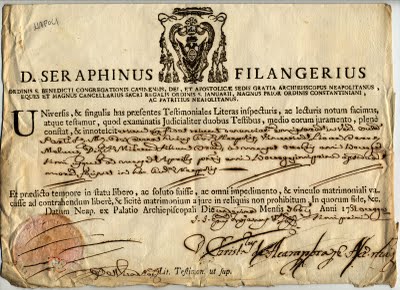

The Golden Eagle and bells in the arms of the Nine Filangeris of Sicily, and the nine rings on the shield of Sicily

A lot has been written about the Filangeris and the insurrection of the Sicilian Vespers over the seven centuries since the event. But as much has been written about it, the origin remains unsolved. Was it a popular uprising or the result of a conspiracy?

The following has been translated from Italian to English using translation software, so the grammar might be a little iffy:

_____________________________________________

Even after the event circulated two different versions: one linked to yet another indignity suffered by a Sicilian woman at the hands of the French, which would have triggered a popular backlash of unusual violence and turmoil that simple would turn into revolution, and that of provocation on the part of a group of Sicilians who, waving a flag whose Pisa exposure had been prohibited by the constitutional authority, would have caused the reaction of the Angevin militias triggering the riot quickly degenerated into open revolt.

This is not the case to revisit the arguments of both current of thought, however, A further element of reflection in favor of the latter seems to introduce the Heraldry.Subsidiary On the origins of the discipline of history, born from the need to locate in the battle to the enemy’s army friends through unequivocal marks, it is variously argued, but certainly the rules used to indicate a stable families of chivalry, for contraddistinguerne the degree of nobility and family relations were regulated in a systematic way by Louis VII and Philip Augustus of France as early as the thirteenth century society in a military-type based on the hierarchical relationships of the feudal vassalage as it was, the signs were not the result of choices impromptu or personal vanity, but found themselves in a logical and formal sovereign grant legitimacy to be brought.

The same military that long distinguished feudalism meant that the granting of certain signs, or their integration with other elements, remember, special acts of bravery or loyalty rendered to a sovereign. Sometimes these concessions took place – significantly – on the same battlefield; other cases, and for reasons of political expediency, and they followed procedure more reserved. A second category we enter the Sicilian branch of the family Filangeris, an ancient family of Norman origin who settled in southern Italy and Sicily in the second half the eleventh century.

Weapons of this family are composed of a silver cross loaded nine bells battagliate in black on a red field. (To see the picture click here) Just nine bells battagliate black (instead absent in the arms of the Neapolitan branch of the family) seem to bear witness to the role that this family was in the story of the insurrection in Palermo on Easter Monday 1282. All ‘era of the revolt, in fact, Palermo had only nine parishes and it is known that during the insurrection antiangioina, the sound of the bells of the parish churches, united to those of the Church of the Holy Spirit placed outside the city walls, called collection to the people, as was the case only in cases of exceptional gravity.

Coincidence between the number of parishes and number of bells present on the arms of Filangeris of Sicily seems too forced to not be the result of a concrete relation of cause and effect. On the other hand it is known that Richard II Filangeris, banished from the Kingdom by Charles I of Anjou since 1266, was exiled from the court’s time Aragonese. One of his presence in Palermo at Easter of 1282, therefore, presupposes his illegal entry in the island with a specific task and of great importance. Evidently, Peter of Aragon and his wife, Constance of Hohenstaufen, not just recited an important part in the preparation of the uprising, but had to be aware of the possible uncontrolled drift of a revolt whose outcome (and the establishment of free communes in Palermo and other cities in the island that gave birth to the Communitas Siciliae, confirm fears principles of Aragon) was far from obvious.

The presence in Palermo, then, partisans of the cause of the Swabian-Aragonese was pretty sure, although their role in the official version put into circulation by the court Aragon had – for reasons of political expediency – to be silent. The task assigned to Richard II Filangeris, according to the insignia of his family, he had to be to rally the people to feed the insurgency antiangioina and possibly direct it towards a solution in favor of Peter of Aragon and his wife. Evidently the Filangeris was only partially successful in achieving its objectives, but the inclusion in their insignia of the nine bells – figuratively – symbolized the bells of the nine parishes of Palermo and the city itself, testifies to the recognition that the king bestowed on his subjects for their activity.

Perhaps not coincidentally, years later (from May 1301 to May 1302), this link between the cities of Palermo and the House of Filangeris was strengthened by his son and successor Peter and Constance – Frederick III of Aragon – who entrusted their son to a (Abbo) of the same knight charging Bajulo (governor) of the capital of the Kingdom.

251 thoughts on “Nine Filangeris of Sicily”

You must log in to post a comment.